|

By: Daniel Wright

Illustration: Declan Wrede

Demystifying Chemical and Drug Patents

Chemical and drug patents employ a style of claim language that can appear daunting and unnecessarily overcomplicated, but the ability to read and make sense of these documents is a necessary skill to develop when navigating the pharmaceutical world. In this article, we’ll break down the underlying complexities and demonstrate how they’re actually motivated by a surprisingly straightforward strategy that synthesizes common chemical nomenclature with standard patent tactics.

The Value of Staking a Claim in the Pharma World

The economics of the pharmaceutical industry demand an immense upfront investment to push a drug program through discovery, clinical trials, the FDA, and only then, into the market. For the most part, the only thing guarding these potential profits is the IP. While, at the end of this process, the drug company is often manufacturing a single compound, the related patents need to have breadth for the same reason as any other industry: slight variations of the compound and/or its formulation as the administered drug can be equally commercially viable and merit protection. On the surface, though, the strategy of how to claim this breadth can appear alien, even to those familiar with patent jargon.

The economics of the pharmaceutical industry demand an immense upfront investment … For the most part, the only thing guarding these potential profits is the IP. Balancing Specificity and Breadth in Patents

The first and most essential construct to understand when reading chemical and drug patents is the “Markush Structure.” But before exploring what that means and how it’s used, it’s helpful to first understand why it comes into play.

For a successful patent, you need specificity and breadth, but moreover, you need your breadth to be specific. Nebulously claiming all possible and wild variants won’t satisfy the Patent Office’s requirement for sufficient detail, and loose claim language may bump into more prior art than you realize. The standard practices of chemical nomenclature present an interesting challenge to patents. On one hand, a structural formula can communicate a very specific molecule. When drawn out, acetone looks like acetone, and taxol looks like taxol. As written, structures can only mean one thing (or a set of isomers when stereochemistry is ignored). On the other hand, generic terms for classes of molecules or functional groups can be profoundly broad. Just try to imagine all the different things you could draw that would fit the descriptor “alkyl-substituted heteroaryl.” Standard Patent Tactic: Markush Groups

Patents across many industries will often employ something called a “Markush group” to specify their variables. Establishing a Markush group always uses the phrase “selected from the group consisting of…” followed by a finite list of options. For example, a claim regarding a plumbing system might state that a particular valve is “selected from the group consisting of a ball valve, a butterfly valve, and a needle valve.” The term “consisting of” limits the options to only what is provided in the list, so in this example, the valve in question could not be a gate valve. Conveniently, you need not define each of these terms of your Markush group in the claim. They can be defined in the specification or assumed, if their meaning is well established in the art.

Chemical Patent Application: Markush Structures

Chemical patents take advantage of the same approach but further synthesize it with a structural formula to form a hybrid that can be considered a “Markush Structure.” These types of claims always begin with a structural formula that includes variables placed throughout (e.g., X, Y, Z, R1, R2, R3, etc.). Down in the body of the claim, each variable will then be defined by a Markush group, spelling out the often expansive list of possible groups. In this manner, you get to use both the exactitude that a structural formula provides (i.e., what is claimed must have at least express structure as presented) with carefully specified variability by the lists of the Markush groups (using whatever definitions you’ve provided in the specification).

As we expand on the standard patent tactic of using Markush Groups and look specifically at their application in chemical patents, it’s worth noting that many modern chemical patents will eschew the exact Markush Groups phrase "selected from the group consisting of..." explained above to avoid the tediousness of how frequently the phrase would otherwise appear in a typical broad chemistry claim. Some are resorting to simply using “is” in all cases before enumerating options, but you might also see phrases like “selected from” (i.e., leaving out “from the group consisting of”), “chosen from,” or “represents.” In any case, all variants simply seek to fulfill the requirement of describing selection from a closed group of options. You can safely interpret these other terms as equivalent to the proper Markush Group phraseology, just with fewer words. Markush Structure Example

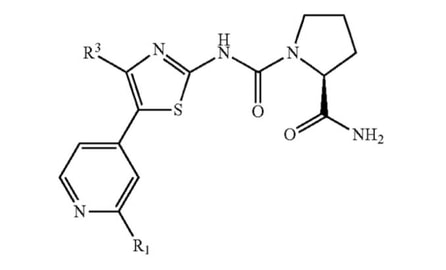

Look at this example of the Markush structure drawn for alpelisib in Pat. No. 8,476,268.

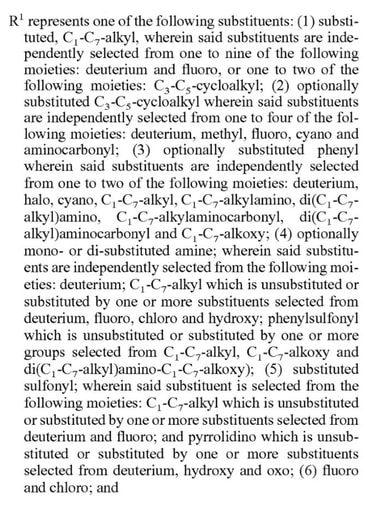

Here, the applicant has narrowed the molecule down to a fairly specific structure. The structural formula locks in the identity, connectivity, and stereochemistry of the three major ring systems and leaves only two variables R1 and R3. A fair amount of breadth, however, can be found in the definitions of these variables. Just take a look at that of R1:

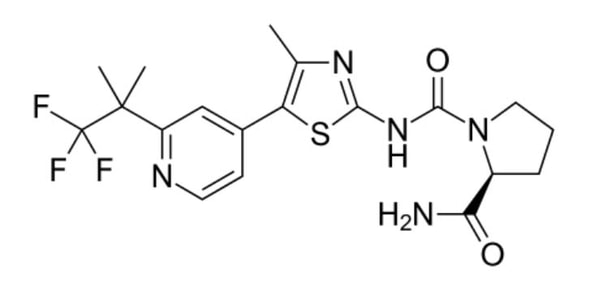

That’s a lot of options, but it’s less than you think. It primarily specifies various alkyl chains and cyclic groups of certain sizes having only a limited set of further substitutions. Looking at the real molecule (shown below) the trifluoro-dimethylethyl group is indeed included there under option (1), but the claim covers so much more without resorting to claiming everything under the sun. Rather, they (presumably) claimed all the specific classes of variants that were of interest.

What goes in the structure versus the variables is the name of the game for patents in the chemical arts. Generally speaking, the structural formula presents the necessary scaffold for the drug or chemical while the variables contain all the options, whether there are two or two hundred. In situations when the structure is already quite narrow, the variable definitions might very well be trying to enumerate immense breadth rather than to further limit the claims. Therefore, paying attention to the structure and connectivity between the variables can often be more illuminating as to the boundaries of the scope. Chemical patents filed early in the drug discovery process may play this strategy a bit fast and loose because the applicant does not yet know what will be critical, but the game is the same. When trying to understand a chemical patent, carefully read through the variables as well as any definitions in the specification all the while noting their positions within the depicted structure.

Other Key Constructs Found in Chemical and Drug Patents

In addition to the above discussion, the following considerations and elements are often found in tandem with a Markush structure claim.

Portfolio Cornerstone for Drug and Chemical Companies

Although method of treatment and method of manufacture claims, not discussed here, can provide strong, alternative coverage (critically so in certain contexts), composition of matter claims, usually defined by a Markush structure, often function as the cornerstone of the portfolio for a drug or chemical company. Therefore, these claims are crafted in a style sometimes daunting in appearance but organized in a consistent manner compatible with the same tactics of breadth of specificity shared by all patents.

This primer will hopefully get you well on your way to clarifying and taking meaning from the chemical and drug patents on your reading list, but as always, don’t hesitate to reach out with more specific questions you may encounter along the way. Related Reading

This is Part 2 of an ongoing series focused on life science patents. If you found this valuable, we highly recommend checking our Part 1: Drug patents and the FDA: Timelines, Exclusivity, and Extensions. Later this month, we'll also being doing a podcast episode that takes a deep dive on fortifying your valuable life science patents.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Ashley Sloat, Ph.D.Startups have a unique set of patent strategy needs - so let this blog be a resource to you as you embark on your patent strategy journey. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed