|

By: Josh Sloat

S2 Episode 2: Inventor Stories Vol. 1

RISEing with Patents

In this month’s special episode, we’re sharing a great sit down with three very innovative, up-and-coming inventors – as we also launch the next installment of our RISE award. We are joined today by:

These inventors share their stories and provide invaluable tips and advice, much learned the hard way. Along the way, we explore:

Availability

Patently Strategic is available on all major podcasting directories, including Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Google Podcasts. We're also available on 12 other directories including Stitcher, iHeart Radio, and TuneIn, so you should be able to find us wherever you listen to podcasts.

Topic and guest participant requests

If you’re an agent or attorney and would like to be part of the discussion or an inventor with a topic you’d like to hear discussed, please reach out.

Resources

We're also providing computer-generated transcripts for improved accessibility and additional reference opportunities. 2022 RISE Award

The RISE award offers a free provisional U.S. patent application or $5,000 towards a non-provisional U.S. patent application to a selected applicant. We're taking applications until May 1st. If your startup could benefit from this award or you know of another innovator who could, use the button below to learn more and apply.

0 Comments

By: Daniel Wright

Illustration: Declan Wrede

Demystifying Chemical and Drug Patents

Chemical and drug patents employ a style of claim language that can appear daunting and unnecessarily overcomplicated, but the ability to read and make sense of these documents is a necessary skill to develop when navigating the pharmaceutical world. In this article, we’ll break down the underlying complexities and demonstrate how they’re actually motivated by a surprisingly straightforward strategy that synthesizes common chemical nomenclature with standard patent tactics.

The Value of Staking a Claim in the Pharma World

The economics of the pharmaceutical industry demand an immense upfront investment to push a drug program through discovery, clinical trials, the FDA, and only then, into the market. For the most part, the only thing guarding these potential profits is the IP. While, at the end of this process, the drug company is often manufacturing a single compound, the related patents need to have breadth for the same reason as any other industry: slight variations of the compound and/or its formulation as the administered drug can be equally commercially viable and merit protection. On the surface, though, the strategy of how to claim this breadth can appear alien, even to those familiar with patent jargon.

The economics of the pharmaceutical industry demand an immense upfront investment … For the most part, the only thing guarding these potential profits is the IP. Balancing Specificity and Breadth in Patents

The first and most essential construct to understand when reading chemical and drug patents is the “Markush Structure.” But before exploring what that means and how it’s used, it’s helpful to first understand why it comes into play.

For a successful patent, you need specificity and breadth, but moreover, you need your breadth to be specific. Nebulously claiming all possible and wild variants won’t satisfy the Patent Office’s requirement for sufficient detail, and loose claim language may bump into more prior art than you realize. The standard practices of chemical nomenclature present an interesting challenge to patents. On one hand, a structural formula can communicate a very specific molecule. When drawn out, acetone looks like acetone, and taxol looks like taxol. As written, structures can only mean one thing (or a set of isomers when stereochemistry is ignored). On the other hand, generic terms for classes of molecules or functional groups can be profoundly broad. Just try to imagine all the different things you could draw that would fit the descriptor “alkyl-substituted heteroaryl.” Standard Patent Tactic: Markush Groups

Patents across many industries will often employ something called a “Markush group” to specify their variables. Establishing a Markush group always uses the phrase “selected from the group consisting of…” followed by a finite list of options. For example, a claim regarding a plumbing system might state that a particular valve is “selected from the group consisting of a ball valve, a butterfly valve, and a needle valve.” The term “consisting of” limits the options to only what is provided in the list, so in this example, the valve in question could not be a gate valve. Conveniently, you need not define each of these terms of your Markush group in the claim. They can be defined in the specification or assumed, if their meaning is well established in the art.

Chemical Patent Application: Markush Structures

Chemical patents take advantage of the same approach but further synthesize it with a structural formula to form a hybrid that can be considered a “Markush Structure.” These types of claims always begin with a structural formula that includes variables placed throughout (e.g., X, Y, Z, R1, R2, R3, etc.). Down in the body of the claim, each variable will then be defined by a Markush group, spelling out the often expansive list of possible groups. In this manner, you get to use both the exactitude that a structural formula provides (i.e., what is claimed must have at least express structure as presented) with carefully specified variability by the lists of the Markush groups (using whatever definitions you’ve provided in the specification).

As we expand on the standard patent tactic of using Markush Groups and look specifically at their application in chemical patents, it’s worth noting that many modern chemical patents will eschew the exact Markush Groups phrase "selected from the group consisting of..." explained above to avoid the tediousness of how frequently the phrase would otherwise appear in a typical broad chemistry claim. Some are resorting to simply using “is” in all cases before enumerating options, but you might also see phrases like “selected from” (i.e., leaving out “from the group consisting of”), “chosen from,” or “represents.” In any case, all variants simply seek to fulfill the requirement of describing selection from a closed group of options. You can safely interpret these other terms as equivalent to the proper Markush Group phraseology, just with fewer words. Markush Structure Example

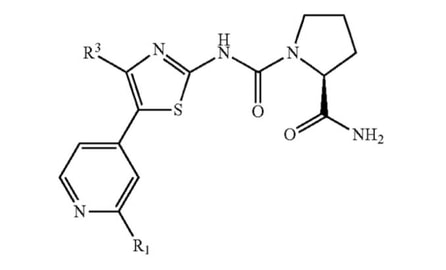

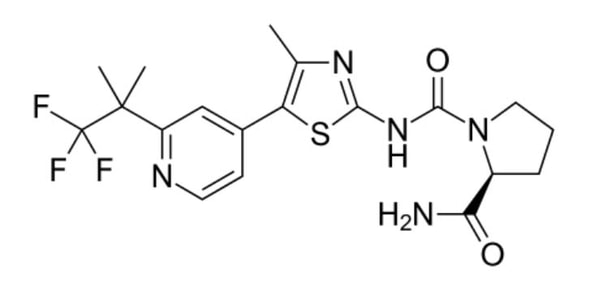

Look at this example of the Markush structure drawn for alpelisib in Pat. No. 8,476,268.

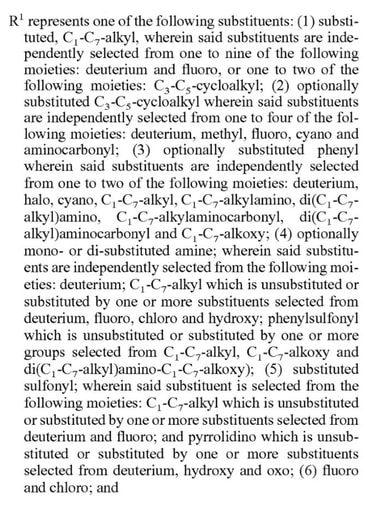

Here, the applicant has narrowed the molecule down to a fairly specific structure. The structural formula locks in the identity, connectivity, and stereochemistry of the three major ring systems and leaves only two variables R1 and R3. A fair amount of breadth, however, can be found in the definitions of these variables. Just take a look at that of R1:

That’s a lot of options, but it’s less than you think. It primarily specifies various alkyl chains and cyclic groups of certain sizes having only a limited set of further substitutions. Looking at the real molecule (shown below) the trifluoro-dimethylethyl group is indeed included there under option (1), but the claim covers so much more without resorting to claiming everything under the sun. Rather, they (presumably) claimed all the specific classes of variants that were of interest.

What goes in the structure versus the variables is the name of the game for patents in the chemical arts. Generally speaking, the structural formula presents the necessary scaffold for the drug or chemical while the variables contain all the options, whether there are two or two hundred. In situations when the structure is already quite narrow, the variable definitions might very well be trying to enumerate immense breadth rather than to further limit the claims. Therefore, paying attention to the structure and connectivity between the variables can often be more illuminating as to the boundaries of the scope. Chemical patents filed early in the drug discovery process may play this strategy a bit fast and loose because the applicant does not yet know what will be critical, but the game is the same. When trying to understand a chemical patent, carefully read through the variables as well as any definitions in the specification all the while noting their positions within the depicted structure.

Other Key Constructs Found in Chemical and Drug Patents

In addition to the above discussion, the following considerations and elements are often found in tandem with a Markush structure claim.

Portfolio Cornerstone for Drug and Chemical Companies

Although method of treatment and method of manufacture claims, not discussed here, can provide strong, alternative coverage (critically so in certain contexts), composition of matter claims, usually defined by a Markush structure, often function as the cornerstone of the portfolio for a drug or chemical company. Therefore, these claims are crafted in a style sometimes daunting in appearance but organized in a consistent manner compatible with the same tactics of breadth of specificity shared by all patents.

This primer will hopefully get you well on your way to clarifying and taking meaning from the chemical and drug patents on your reading list, but as always, don’t hesitate to reach out with more specific questions you may encounter along the way. Related Reading

This is Part 2 of an ongoing series focused on life science patents. If you found this valuable, we highly recommend checking our Part 1: Drug patents and the FDA: Timelines, Exclusivity, and Extensions. Later this month, we'll also being doing a podcast episode that takes a deep dive on fortifying your valuable life science patents.

By: Josh Sloat

About the MasterClass Event

Aurora is once again partnering with our good friends at InnovatorMD as part of new program called InnovatorMD University. This is a year-long program consisting of 40 Master Classes designed to educate healthcare innovators and entrepreneurs on essential topics. Each Master Class is hosted by Uli K. Chettipally, MD, MPH. and will feature an expert, who is the Instructor for that Master Class.

Prenuptial Patenting

Responsible Engagement with Engineering Firms You have your big idea and now it’s time to breathe it into existence, but you need some help with the development. In this talk, we discuss everything you need to know before and during the course of engaging with an engineering firm. We’ll cover IP ownership, assignment from engineering firm inventors back to you, and how to avoid the traps of viral IP. Time and location: Thursday, March 24, 2022 | 5:00 PM - 6:30 PM PT | Live Webinar via Zoom

By: Daniel Wright

Illustration: Declan Wrede

FDA and Patent Timeline Mismatch

In its mission to protect citizens from faulty or fraudulent products, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) requires you to submit substantial proof of both efficacy and safety of your new pharmaceutical or medical device before it can be legally sold in the United States. Collecting these data in clinical trials and the subsequent review process takes years, sometimes over a decade, and if there’s a patent involved, it’ll likely issue well before the FDA gives you the green light. This can seem more than a bit unfair since that patent term is supposed to provide the economic exclusivity needed to recuperate the fortune expended on drug development. Rest assured, the FDA is aware of this counterproductive interaction and offers a number of compensatory options. First, though, let’s take a look at the patent prosecution and FDA approval timelines for context.

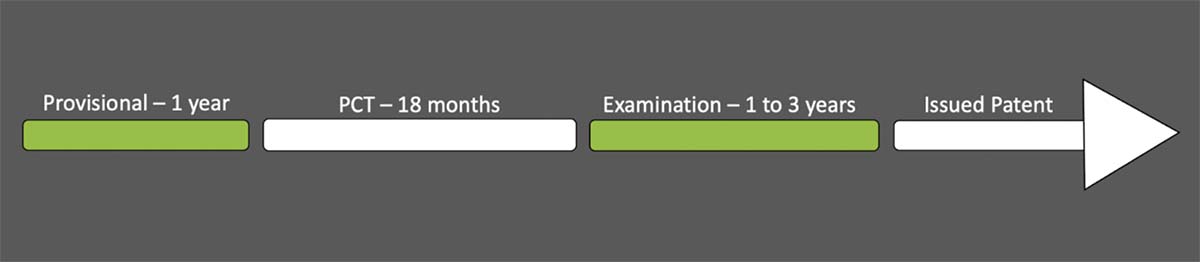

MATCHING PACE: Patent Prosecution Timeline

The patent prosecution timeline has a few options depending on your target geographic market and whether you expedite your application, but shown here is the common path. Most applicants begin with a provisional application that yields an international patent application filing, usually under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT), enabling the application’s entry into foreign jurisdictions. The duration of examination before each local patent office can vary dramatically, but in the U.S., this can take around one to three or more years. Following approval, your issued U.S. patent will remain enforceable for the patent’s term of twenty years starting from your first non-provisional filing date (as long as you keep paying the maintenance fees). Therefore, from start to finish, you’re looking at about four or more years to acquire your issued patent which will last for about sixteen years afterwards (note: the provisional patent application year is not counted in your 20 year patent term).

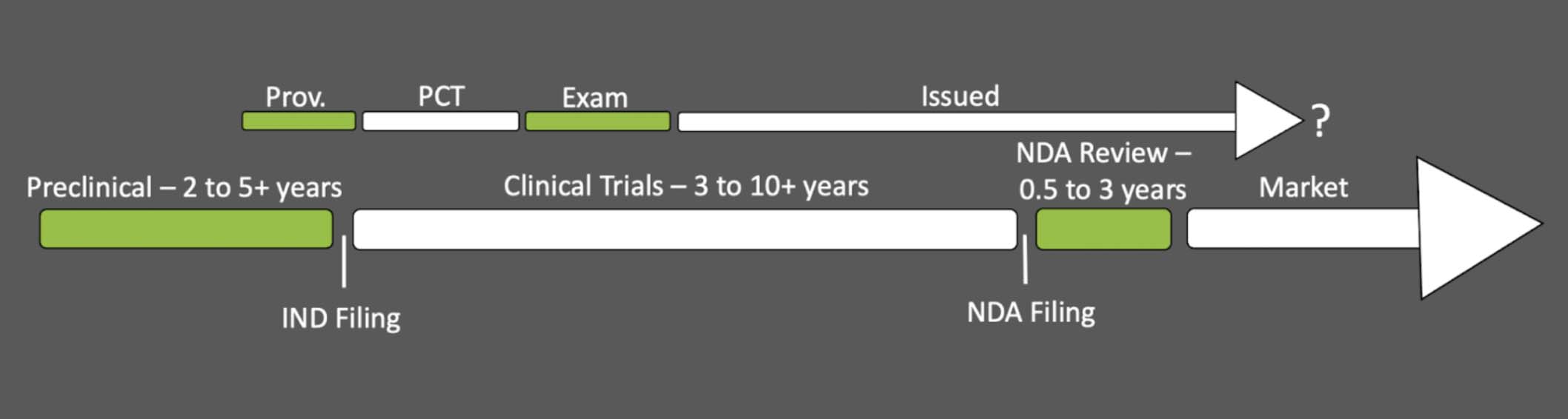

MATCHING PACE: Drug Discovery and Regulatory Timeline

Now, let’s review the other half of this discussion. The patent prosecution timeline can seem a mere blink of an eye in comparison to the duration that drug discovery and the regulatory process demand.

Preclinical research. The process begins in preclinical research. Here, chemists and biologists will decide on their biological target for the disease indication (e.g., which protein to inhibit to treat what illness), and design molecules to test for viable activity (e.g., does it actually inhibit the desired protein). Promising compounds will then be pushed into cell lines and animal models to probe for the drug’s in vivo efficacy, bioavailability, and toxicity.

Investigational New Drug (IND) Application. With promising preclinical results in hand, you can then approach the FDA with an Investigational New Drug (IND) Application. In this document, you present all your evidence that suggests efficacy and safety in humans along with the parameters of your proposed clinical trials. The FDA will review it within thirty days for any unreasonable risk, demanding further experiments if needed, but, in bestowing approval, will authorize you to commence your clinical trials.

Clinical trials will likely be the longest period of this process because of the sheer scope of the undertaking. The mobilization of a sufficient patient population to explore short and long term effects in rigorous studies is not something that can be performed over a weekend, and for most, this operation will take about six to seven years, sometimes longer. New Drug Application (NDA). Ultimately, you will compile your (hopefully) successful clinical trial results along with relevant preclinical insights into a New Drug Application (NDA) that demonstrates the safety and efficacy of your new pharmaceutical towards one or more specified disease indications. The FDA has up to three years to return a final decision. If they find any aspect lacking, they may require additional studies to be performed; otherwise, with approval of the NDA comes your ability to finally sell your new pharmaceutical, perhaps only ten to fifteen years after you started. Note: Medical devices go through a very similar process, and if your drug is a generic of a compound previously approved by the FDA you can likely skip the clinical trials (we won’t be discussing those scenarios here). Patent Prosecution and FDA Timelines Side-by-Side

Having now explored both the patent prosecution and FDA timelines, let’s place them side by side. The exact alignment will depend upon when you chose to file your patent, but for many, the provisional application will be filed sometime near the IND filing due to the somewhat public nature of clinical trials and the concurrent demand for more open advertising and public relations. Accordingly, we end up with a dual timeline that looks something like this:

Very likely, you’ll acquire your issued patent sometime during clinical studies, well before you can enter the market. In the worst case scenario, your issued patent may have less than 5 years of life left when you can finally enter the market with your new drug. Let’s take a look at what the FDA offers as compensation for this less-than-ideal situation.

Options for Maximizing Your Exclusivity Window

In return for the extra regulatory hurdle and the potential lost patent protection time, the FDA offers the following three perks in certain conditions:

Patent Term Extension (PTE) means exactly what the words say: bonus term for your patent. Upon approval and at your timely request, the FDA will instruct the United States Patent and Trademark Office to append all of the time spent in NDA review and half the time between the IND and NDA filings to a single relevant patent. Up to a combined total of five years can be added, and the remaining lifetime of the chosen patent, after the addition, cannot exceed fourteen years. Furthermore, only the relevant claims enjoy the extension, so if your selected patent claims three discrete compounds separately, only the one towards the approved drug gets extended. The remaining two perks function independently of any related patents and instead only affect the FDA’s operations in your favor. New Chemical Entity (NCE) Exclusivity is an award to new “active moieties” of a five-year period in which the FDA will not accept any competing applications (usually an application for a generic of your drug). This means that, even if you have no patent on the drug, your successful FDA approval grants you a functionally similar limited monopoly on the market while the regulatory agency refuses to even initiate the process with competitors. Note that the FDA considers the “active moiety” of a drug to be the biologically active chemical entity regardless of any formulation, salt, or prodrug. If you’re working with any of the latter, you’ll be interested in what’s next. New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity is a three-year period in which the FDA will not approve competing applications. New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity is awarded to successful cases that involve a previously approved active moiety but had required new clinical studies. Applications that repurpose an old drug in a new formulation, prodrug, dosage, or towards a new disease indication can all qualify, but keep in mind that this perk is necessarily narrower than NCE Exclusivity. Assuming there’s no broader protection for your product, competitors could avoid your New Clinical Investigation Exclusivity by remaining with an older, unprotected formulation or marketing their generic only towards previously approved diseases. Start synchronizing your timelines…first steps to restful nights

The FDA certainly adds a whole other layer of complexity to the question (and we did not discuss here more niche perks such as those to pediatric or orphan drugs nor the nuanced tactics competitors can try to circumvent the various FDA exclusivities), but it’s comforting nonetheless that the agency is aware of the barrier its efforts present to the patent system and its motivating economic incentives. Certainly, you should discuss your filing strategy with your practitioner before committing to any plan, but you can sleep soundly knowing that some options remain even if your patent issues (or worse yet, is near expiration) well before your drug is on the market.

|

Ashley Sloat, Ph.D.Startups have a unique set of patent strategy needs - so let this blog be a resource to you as you embark on your patent strategy journey. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed