|

By: Daniel D. Wright

Patenting in the fog of unknowns

Application disclosure requires a certain level of specificity and scope restraint to satisfy Written Description and Enablement requirements, but rarely is the route from prototype to product a clear and straight line. Especially in biotech, R&D can take you all over the map, and the full picture develops slowly as the data amasses and candidates rise and fall in favor.

In our previous post on provisional patent applications, we explored the valuable flexibility of provisional applications but described the dangers of being too casual with the disclosure. A related concern stalks patent applications at all stages of prosecution – provisional or otherwise. When does imagination and, more insidiously, hindsight overreach the due scope of your application?

Disclosure Requirements

The Written Description and Enablement requirements, both encoded into 35 U.S.C. 112(a), establish the legal basis for your application’s disclosure, and therefore, what justly can be claimed. As two separate requirements with two different motivations:

Satisfying Both Requirements: Live Together, Die Alone

Though closely related, you can meet or fail these rules independently. Stating what the invention is with no context or instruction meets the written description requirement but fails the enablement requirement, and providing a laundry list of techniques and options for its construction or use without ever clearly stating what the invention is meets the enablement requirement but falls short of the written description requirement.

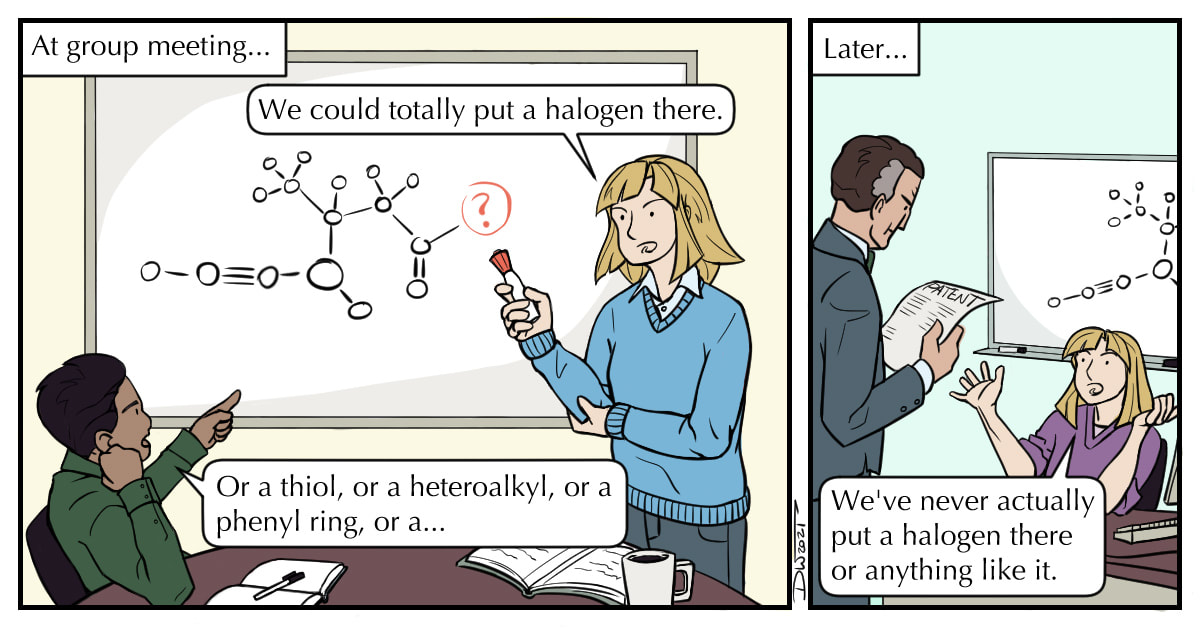

IRL: Business Demand v. Available Data

In chemical and pharmaceutical patents, it’s easy to outpace your own invention and run afoul of one or both of these rules. The story normally goes like this. In the early stages of a drug program, the business demand for IP outpaces the collected data. You might have a vague molecular scaffold in mind, but the present data availability is not sufficiently clear to know the boundaries of what’s viable, let alone what specific groups or variants will yield your lead candidate. Considering the ease of imagining all the possible variables, you might try to stretch those variable positions to be maximally inclusive beyond the reasonable scope of your data.

Hindsight is (like the year) 2020

This can facilitate the temptation to “figure it out later” and to argue that as long as all the broad terms (e.g., alkyl, heteroalkyl, etc.) are in there, you can narrow it to the valuable bits by piecemeal selection in prosecution when you have had more time to collect more data. At the end of that road, though, you’ll often find that this hindsight-fueled strategy often breaks one or both of these requirements.

Lesson from the Courts

Novozymes: A cautionary tale of disclosure scope

Novozymes A/S v. DuPont Nutrition Biosciences APS, No. 12-1433 (Fed. Cir. July 22, 2013) shows an instance of clearly overrunning the mark. Novozymes had filed an application outlining numerous possible variants of alpha-amylases derived from genus Bacillus bacteria with the variants purported to exhibit improved stability at industrially relevant conditions. The application lists seven parent enzymes with extensive mutations possible at one or more of thirty-three positions. Considering the tremendous breadth of possibility described and lack of commensurate data, Novozymes ultimately failed to acquire a patent in their first efforts during prosecution, encountering difficulties with both the enablement and written description requirements. If at first you don’t succeed... Meanwhile, DuPont successfully engineered a modified alpha-amylase having superior stability under the desired conditions and secured it with a patent. Upon noting that DuPont’s site of mutation was among the thirty-three listed in their own disclosure (although an express mention of the specific mutation was not), Novozymes filed a continuation application with new claims directed to that class of variants, thereby covering the specific enzyme of DuPont. This time, they succeeded in acquiring a patent and soon filed an infringement suit against DuPont. Just cause the PTO says... Before the court, DuPont pressed hard on their written description and enablement weak points. They demonstrated that in addition to the absurd wealth of possible embodiments, Novozyme’s disclosure contained no successful embodiment of the claimed class of enzymes. Siding with Dupont on appeal, the court weighed in heavily against Novozymes’s hindsight-informed approach: Taking each claim … as an integrated whole rather than as a collection of independent limitations, one searches the [application] in vain for the disclosure of even a single species that falls within the claims or for any “blaze marks” that would lead an ordinarily skilled investigator toward such a species among a slew of competing possibilities. “Working backward from a knowledge of [the claims], that is by hindsight,” Novozymes seeks to derive written description support from an amalgam of disclosures plucked selectively from the [application].

Although the USPTO is comparatively generous with revised or new claim language, your claims must still reflect a singular invention, duly described and present from the start. Thus, when you file a patent application, provisional or otherwise, you must do so seeking a property right for an invention in hand, not one that you’ll divine later.

When you file a patent application, provisional or otherwise, you must do so seeking a property right for an invention in hand, not one that you’ll divine later. The Constraint Takeaway

R&D often takes you to wild places not apparent at the start of the journey when you filed your first application, and it can be tempting to try to shoehorn recent developments into established filing dates. Sometimes that might be what you need to do, even with the above risks in mind. However, first consider whether those new revelations can stand on their own as a fresh filing. Since they weren’t expected at the start, they just might be novel and non-obvious enough to stand over your previous work, earning you a new patent term. To this end, take care to structure and schedule your applications accordingly so that each advancement of your tech is given the due space and support it needs, as broadly or narrowly as it deserves. Hindsight is seldom your friend in these matters.

1 Comment

David Cohen

2/17/2021 01:38:46 pm

I think the article comes down a little too hard on the Provisional as the problem. Not sure, but it sounds like Novozymes may have rendered their provisional directly or nearly directly in to a regular application. If Novozymes had a better grip on the invention before filing the regular, then the error was not necessarily in the provisional, but in not updating the regular, or in filing a follow up provisional.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Ashley Sloat, Ph.D.Startups have a unique set of patent strategy needs - so let this blog be a resource to you as you embark on your patent strategy journey. Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed